陳文苑

歌舞片始於三十年代的香港影壇,成為當時其中一種大受歡迎的電影類型。這種以歌唱與舞蹈形式混合、充滿歡快氣氛的片種,透過歌聲和身體上的伸展擺動,表達角色心情,發展一段又一段動人故事,基於這種呈現形式,普羅大眾對於歌舞片的印象,都偏向建構在正向思想,預設男主女角會步向完滿的結局,然而,歌舞片在香港的起源不能只單純視之為一種電影創作類型,它所牽涉到的是當時香港社會發展脈絡和女性面對的窘境,在這些歌舞昇平的背後,原來是暗湧處處。本文將探討歌舞片當時紮根香港的原因,它又是如何發展出獨有的特色,建構出與外國歌舞片不同的風格,從中比較兩者的不同之處。

香港歌舞片的源起,其實來自於一個稱為「歌舞團」的群體,它的出現為本地歌舞片提供主要養份。但在華麗光鮮背後,卻藏着不少淒慘的故事。三十年代開始歌舞團出現,成為當時女性脫離困局的新一種工作選擇。相對男性而言,女性生存技能較少,無以為生,加上打仗時流離失所,入歌舞團對他們來說,在生活和工作上,帶給她們不同的可能性。另外,直到1935年前港督貝璐宣佈禁娼前,香港娼妓風氣依然盛行,當時香港風月場所共有200多家,遍佈全港九,有部份女性被迫良為娼[1],正如阮玲玉主演的《神女》(1934)一樣[2],婦女受生活所迫,最後成為暗娼,飽受屈辱,這等情況在現實同樣活生生存在。在禁娼以後,風月場所演變成另一種形式−−「導遊社」。這些導遊社源自於上海,當上海淪陷後,便轉移至香港[3],直到1939年期間,香港共有80多間導遊社,而其服務也不只限於賣身,甚至包括經營浴室、按摩、修甲等等[4],當時甚至出版了一本名為《香港導遊專刊》的刊物,專門介紹導遊女。[5]

但禁娼以後,也有不少人「上岸」改行當歌女或舞女[6],因為相比起被強行出賣肉體換取金錢,這無疑是另一條出路。當時香港興起了一種名為「歌舞團」的產物,所謂歌舞團,是在二十年代末開始至三十年代初由上海興起的劇團和音樂團體,這類團體大多數都活躍於劇場和廣播當中,團員皆是歌女。以「賣藝」取代「賣身」,雖然歌舞團也必然有它的黑暗面,相信對於當時女性來說,仍是個吸引條件,既可脫離困境,也能投身演藝事業,無疑成為女性遠離混沌的可能性。另外,也有不少女性是懷抱着歌舞夢,不怕艱辛堅持追夢,在舞台發光發亮。筆者推斷不少女性也視之為跳板,開闢工作新路徑,就三十年代香港歌舞片的內容題材,便足以論證這一點。

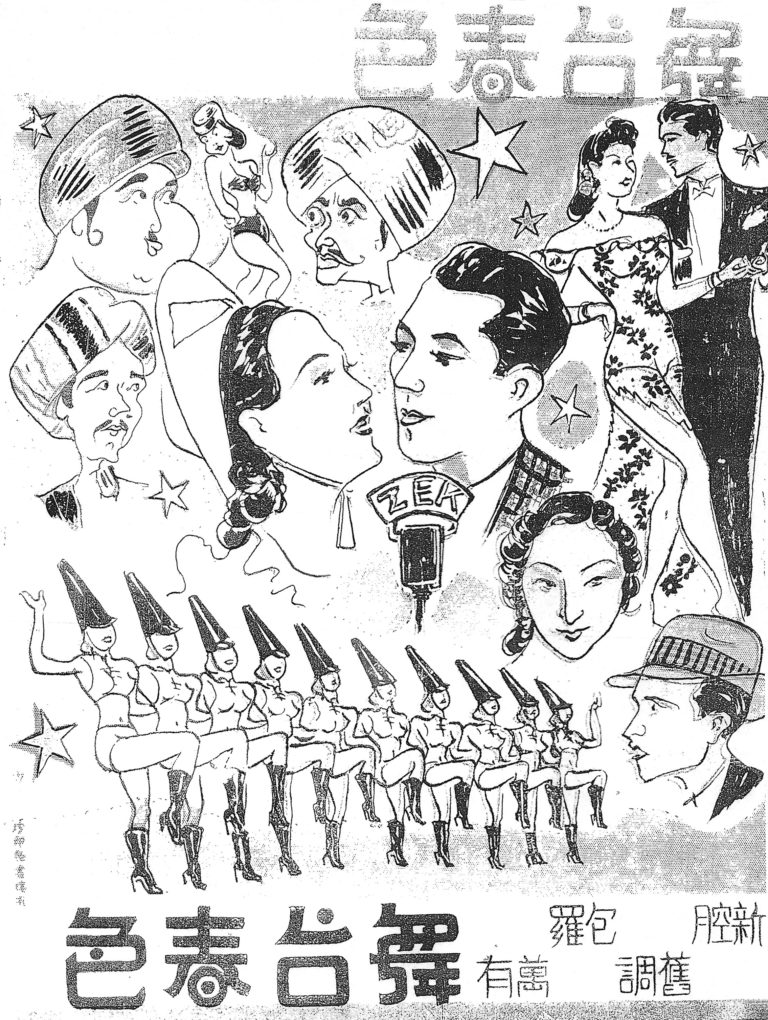

由湯曉丹執導、許嘯谷編劇的《舞台春色》(1938)故事正是以歌舞團作為背景。講述女主角林愛玲熱愛表演,於是向藝花歌舞團自薦,卻遭班主倫拒絕,後來劇團因為演員宋麗麗失場,失去表演合約,飽受抨擊。另一邊廂,被拒絕的林愛玲繼續發奮圖強,在佛氏三兄弟的訓練下,愛玲終於得到馬倫賞識。但由於劇團經濟狀況不穩,馬倫和愛玲二人只得暫時在播音台演唱,演唱大受歡迎,二人也日漸生情[7]……這部電影直接描述歌舞團現實的光明和黑暗面,也表現了女性願意為理想奮鬥,不怕艱辛的形象(見圖一)。

正如前文所提及,參加歌舞團是女性的新工作選擇,當時也有電影公司看準這個時機,設立歌舞班,招攬有才華的女性加入,南粵正是例子。公司曾招攬數十個具有才藝的妙齡姑娘,加以訓練[8],另也有登報招考,以及從華南有名氣的戲劇團體中選拔人才。[9]訓練內容十分嚴謹,每天定時從下午二時開始,四時結束,而且按身高和體格分組,由高至矮、由最高等至最次等,以保障電影歌舞呈現一定水平。當時南粵招徠了數十位妙齡姑娘,當中年紀最小的只有十四五歲,包括楚湘雲、鄧靜嫦、陳安娜等人,培訓了一班明日之星,在舞台上大放異彩。

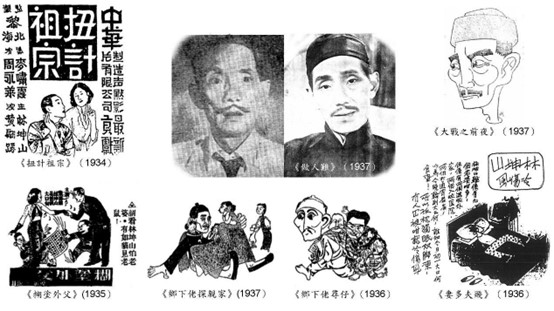

正如前文所提及,當時歌舞電影的主題,並非一味以正向思想為主,在歌與舞的背後,更是充分反映社會實況。以由陳皮執導的《神祕之夜》(1937)為例,故事講述當時城市中斑駁陸離的情況,神秘之夜特刊中提及:「充滿了靈肉刺激!暴露了世界隱秘面!」[10](見圖二),在女性的形象塑造上,這部影片的女性角色大多數是逃學女學生、街頭妓女、在舞場流連陶醉在愛戀中的女性,《神秘之夜》原名為《黑暗世界》[11],充份反映了社會的悲情和陰暗面。《神祕之夜》全部對白都以歌唱形式唱出[12],從當年《南粵》特刊所見,不少曲目名稱也與女性遭遇相關,例如〈索女招待〉,更附有一小段介紹:「女侍本為婦女職業之種,但狂且之徒,輒從而蹂躪之;於萬目睽睽之下,大庭廣眾之中,每嬉皮笑臉,作穢語污言⋯⋯」[13],也有另一首則是〈調戲女工〉,「何少雄癩蝦蟆想食天鵝肉。藉發粮以要脅女工。更且作得隴望蜀一箭三鵰之想⋯⋯」[14](見圖三),電影描述了當時女性遇到的困境,寫實反映城市中陰霾角落。

但隨着歌舞團的流行和香港社會逐漸開放進步,香港三十年代歌舞片變得多樣化,不只是一味反映社會的陰暗面。當時不少國內和外國歌舞團訪港,發跡自上海和廣州的歌舞團曾多次到訪香港表演,例如梅花歌舞團曾在1933年訪港[15],在太平戲院登台,並表演《盤絲洞》、《楊貴妃》、《璇宮艷史》、《後台》等等,而在1935年,梅花歌舞團再次造訪,並連續三天在高陞戲院登台演出[16],演出《漁光曲》、《草裙艷舞》、《丁香山》等曲目,報章以「精彩」和「盛況」形容其演出,可見市民大眾對於歌舞文化已有一定喜愛和接受度。

除華人的歌舞團以外,外國歌舞團也曾到訪香江。一九三三年六月二十一日的《工商日報》便以「荷理活歌舞團又來了」為標題[17],為當時在全球環遊聞名的美國歌舞團大肆報導,本來歌舞團只是路經香港,不打算逗留表演,但經過太平戲院連番挽留,終於在本港演出四天,而記者更稱「聞此次所演盡是風騷香艷」,「更精彩、更肉感」,不但反映了外國歌舞團的特色,更見這種開放的演出為港人所接受。在一九三六年,中央戲院亦主動邀請德國男女藝術團到港表演[18],報導將其形容為「驚人技藝」、「目眩神迷」,更誇張為「看過之後,莫不同聲讚美」,而值得令人注意的,是次表演特意放在歌舞片《荷理活狂歡會》(Hollywood Party, 1934)的放映期內。[19]

歌舞片的呈現亦開始吸納外國元素在其中。1935年上映的《紅伶歌女》(Opera Stars and Song Girls)正是好例子。故事設定上,由謝醒儂飾演的舞臺紅伶因為失業,加上要照顧生病的母親和妹妹,只能屈就於街頭幫人擦鞋養活。但憑着一把美妙的嗓子,為他帶來不少生意,也得到劇團班主賞識與當時知名歌女陳雪香合演歌舞劇《鬧婚》。其次,在這段「戲中戲」中,採用了新派美國百老匯式歌舞劇,由廣州及香港的舞女們扮演成宮娥,但身上穿着西式服裝,戴蝴蝶頭盔,而謝醒儂則穿戴西方白馬王子的服飾。《紅伶歌女》在1935年3月4日在娛樂大戲院試映[20],當時報章形容其為「導演手法純熟、光線及聲音置景較該公司過去出品更為進步」、「音樂方面允另闢新途徑」,被評為「觀眾極為稱賞」,本着立意深刻,寫當時紅伶和歌女們在困境下仍然以完成戲劇使命為大原則[21],難怪在上映一個月後,觀眾仍然「人山人海」、「入座甚為踴躍」。[22]

而女性在電影中的服飾、打扮上打破傳統框架,跳進西方文化,得到解放。例如《舞台春色》專刊宣傳形容為這部片「攝製三月,耗資五萬,歌舞十場,美女二百」,從劇照亦見片中排場聲勢浩大,不論是舞蹈姿勢,排位、服飾都和荷里活製作十分相像,電影雜誌除劇照外,也有加上插畫,這些插畫惟肖惟妙,把片中的佛氏三兄弟畫成印度人裝扮,頭包白布,半裸上身,而林愛玲則被繪成穿着性感、蒙着臉紗的女郎,動作婀娜多姿。(見圖四)而片中所唱的曲譜,也展示在專刊中。

而1939年上映、創下當年香港最高票房紀錄的《第八天堂》[23],由唐雪卿和薛覺先主演。講述由女主角飾演的粵劇名伶擇夫趣事[24],而且片中多用歌曲穿插在劇情當中,不知是巧合還是有意,當年電影上映時間擇在聖誕節,當年報章更稱是「一個盛大的銀色禮物」[25],在宣傳上,這部歌舞片配合了外國最重要的節日之一——聖誕節,將西方元素融入其中。而劇照中亦見女主角唐雪卿身穿西式戲服,身旁侍女們也穿着類似服裝,唐雪卿身處中心猶如萬花簇中(見圖五),其服飾打扮及舞台姿勢都與外國歌舞片有異曲同工之妙;然而,除了仿效西方外,電影仍能保持東方基調,從劇照中可見,男女主角薛覺先和唐雪卿在某些情節會身穿粵劇服裝唱粵曲。

總結而言,三十年代香港歌舞片的源起和發展,與女性的處境際遇息息相關,從被壓迫到躍上舞台,以歌舞表現社會和反映自身面對的狀況,及後更能藉由此打破傳統對女性的印象,逐漸開放步向西化。而在電影的基調上,三十年代歌舞片仍保留華人特色,沒有「走調」,及後到四十年代開始,歌舞片依然發展盛行,周璇在港拍的電影是彩色歌舞片《彩虹曲》(1953,新華),據說是首部中國彩色歌舞片。新華拍攝歌舞片也出名,如向電懋借林翠拍的《碧水紅蓮》(1960),赴台灣及日本取景,並在日本拍攝海底特技及由日藉歌舞演員參加演出。另有不少女明星如葛蘭、林翠因能歌善舞而受到矚目,風靡一時,在電懋和邵氏誕生後,更將歌舞片的特色推到最高鋒,讓這種既有異國風情,又能影射華人文化的片種發揚於本土和海外。

- 劉瀾昌:在河水井水漩渦之中: 一國兩制下的香港新聞生態(增訂版) 。台灣:秀威資訊,2018,頁165。 ↑

- 張偉:《談影小集——中國現代影壇的塵封一隅》。台灣:秀威資訊,2009,頁151。 ↑

- 楊國雄:《舊書刊中的香港身世》。香港:三聯書店(香港)有限公司,頁75。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 同註3。 ↑

- 邵雍:《中國近代妓女史》。上海:上海人民出版社,2006,頁313。 ↑

- 黃淑嫻、郭靜寧編:《香港影片大全第一卷(1914-1941)》(增訂本)。香港:香港電影資料館,2020,頁295。 ↑

- 史東:〈漫談南粵歌舞班中三雛燕〉,《南粵》第8期,1938年12月10日。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 《神秘之夜特刊》,1937年。 ↑

- 黃淑嫻、郭靜寧編:《香港影片大全第一卷(1914-1941)》(增訂本)。香港:香港電影資料館,2020,頁157。 ↑

- 同註10。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 〈蓮花歌舞團 攝影春畫〉,《天光報》 1933年6月20日 。 ↑

- 〈高陞演梅花歌舞團〉,《華字日報》1935年4月5日。 ↑

- 〈荷里活歌舞團又來了〉,《工商日報》1933年6月21日。 ↑

- 〈中央院續演歌舞團〉,《華字日報》1936年4月7日。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 〈紅伶歌女成績超絕〉,《工商日報》1935年3月5日。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

- 〈東樂仍映紅伶歌女〉,《工商日報》1935年4月2日。 ↑

- 魏君子:《光影裡的浪花:香港電影脈絡回憶》。香港:中華書局(香港)有限公司,2019年,頁50。 ↑

- 《旎旖風光的第八天堂》,《南粵》第8期,1938年12月10日。 ↑

- 同上註。 ↑

Chan Man-Yuen

Musical films first appeared in Hong Kong cinema in the 1930s and became one of the most popular film genres of the time. The genre was a mixture of singing and dancing with a joyful atmosphere, in which characters expressed their emotions through their voice and body movements, progressively developing into heart-touching stories. Under such a form of presentation, the general public’s impression of musicals tended to focus on the positive aspects, presuming that the hero and the heroine would reach a happy ending. However, the arrival of musicals in Hong Kong cannot be considered merely as a new film genre, but it involved the social development of Hong Kong and the dilemmas faced by women at the time. Hidden behind all the singing and dancing were, in fact, undercurrents. This article will explore why musical films took root in Hong Kong at the time and how they developed their distinctive characteristics and constructed a style that differed from foreign musical films, thereby comparing the differences between the two.

As a matter of fact, Hong Kong musicals originated from a community called the “Song-and-Dance Troupe”, which was the very source for the development of local musicals. However, behind all the splendour and glamour were stories of misery. In the 1930s, the Song-and-Dance Troupe began to develop and became a new alternative for women to get out of difficult situations. Compared to men, women lacked the skills to make a living, coupled with the fact of losing their homes during the war, therefore, joining the troupe would mean new possibilities to them in life and work. Furthermore, until former Governor Peel announced the prostitution ban in 1935, prostitution in Hong Kong was still very common. There were more than 200 brothels at the time all over the city. Some women were forced into prostitution [1], as depicted in the film The Goddess (1934) starring Ruan Lingyu [2], where women ended up secretly working as prostitutes in order to survive, enduring all sorts of humiliation. Such situations did in fact happen in reality. After the prostitution ban, the brothels evolved into another form−the “Tour Guide Agency”. These agencies were originally from Shanghai, but after the fall of the city, they were relocated to Hong Kong [3]. By 1939, there were more than 80 agencies in Hong Kong, and the services they provided were not only limited to sex but also bathhouse, massage, manicure, etc. [4] At that time, they even published a magazine called the Hong Kong Tour Guide Special, dedicated to introducing tour guide girls. [5]

However, after the prostitution ban, many women “mended their ways” by turning to work as singers or dancers [6], since this was an alternative to selling their bodies for money. At that time, a certain Song-and-Dance Troupe began to gain popularity in Hong Kong. Song-and-Dance Troupe was a kind of theatre and musical troupe developed in Shanghai from the late 1920s to the early 1930s, most of them were active in theatre and broadcast, and the members were all female singers. Selling artistic talents instead of their bodies, even though there was still inevitably a darker side to the troupe, was still an attractive option for women at the time as a way for them to escape from their plight as well as to join the show business, thus it was no doubt an opportunity for women to break away from the chaos. Besides, many women dreamed of becoming singers and dancers and were determined to pursue their dreams and shine on stage despite all the hardships. I would deduce that many women saw it as a stepping stone to new career paths, as can be proven by the subject matter of Hong Kong musicals in the 1930s.

In Stage Romance (1938), directed by Tang Xiaodan and written by Hui Siu-kuk, the story is precisely one that is based on the Song-and-Dance Troupe. The heroine, Lam Oi Ling, is passionate about performing, so she puts herself forward to the Art Flower Troupe but is rejected by Ma Lun, the troupe’s master. Later, due to the performance errors of Song Li Li, the troupe loses their performance contract and faced heavy criticism. On the other hand, despite being rejected, Lam Oi Ling continues to strive for excellence. Under the training of the three Fo brothers, Oi Ling’s talent is finally recognised by Ma Lun. But due to the troupe’s financial difficulties, Ma Lun and Oi Ling can only sing on a broadcast for the time being, and their performance is a huge success. As time goes by, the two begin to grow fond of each other[7]… Not only does the film depict the bright and dark sides of the troupe in reality, but it also shows the image of women willing to fight for their ideals despite all the difficulties (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stage Romance (1938) depicts not only the bright and dark sides of the troupe in reality but also shows the image of women willing to fight for their ideals despite the difficulties ( Stage Romance special issue, 1938).

As mentioned above, joining the troupe offered women a new option of work, and some film companies saw the opportunity to set up song and dance classes to recruit talented women, of which Nanyue Film Company is an example. Dozens of talented young women were recruited and trained [8]. Besides, recruitment advertisements were published in the newspapers, and talents were selected from famous theatre troupes in southern China. [9] The training was extremely rigorous, starting at 2 pm and finishing at 4 pm on a daily basis. The groups were established according to height and physique, from the tallest to the shortest, from the highest level to the lowest level, to guarantee a certain standard of performance. At that time, Nanyue recruited dozens of young women, among whom the youngest was only 14 or 15 years old, such as Chu Hsiang-yun, Tang Ching-seung and Chan An-na, and cultivated a group of rising stars who would shine on stage.

As mentioned earlier, the themes of the musicals did not only focus on positive aspects but, more importantly, fully reflected the social reality behind all the singing and dancing. Take A Mysterious Night (1937), directed by Chan Pei, as an example, which tells a story about the colourful diversity in the city at that time, as mentioned in the special issue of the film: “Stimulating for both body and mind! The hidden side of the world is exposed!” [10] (See Figure 2). In terms of the portrayal of women’s image, most of the female characters in the film are truant schoolgirls, street prostitutes, and women drunk on love frequenting dance clubs. A Mysterious Night was originally called The Dark World [11], truly reflecting the tragic and dark sides of society. All the dialogues in A Mysterious Night are sung in form of recitative [12]. As shown in the special issue of South China, many song titles are associated with women’s experiences. For example, the song entitled “The Pretty Waitress “, is accompanied by a short introduction: “Waitress is supposed to be a respectable female profession, but the madman often assaults her; he smirks and makes filthy remarks in public…” [13]. Another is titled “Teasing the Female Worker”, in which “Ho Siu-hung overetstimates himself. He would threaten the female workers with their salary and is so greedy that he wishes to tease three ladies at the same…” [14] (See Figure 3). The film depicts women’s plight at the time and realistically reveals the dark corners of the city.

Figure 2: A Mysterious Night tells a story about the colourful diversity in the city at the time. In its special issue, it was mentioned, “Stimulating for both body and soul! The hidden side of the world is exposed!” (A Mysterious Nightspecial issue, 1937)

Figure 3: Song in A Mysterious Night ( A Mysterious Night special issue, 1937)

However, as singand-dance troupes became more popular and Hong Kong society further developed and opened, Hong Kong’s 1930s musical films became more diverse, reflecting more than just the darker side of society. At that time, many domestic and foreign song-and-dance troupes visited Hong Kong. Song-and-dance troupes from Shanghai and Guangzhou had come to Hong Kong several times to perform. For instance, the Plum Flower Dance Troupe came to Hong Kong in 1933 and performed at the Tai Ping Theatre, where they played Spider Web Cave, Yang Guifei, My Love Parade, Backstage, etc. Later in 1935, the troupe revisited and performed at the Ko Shing Theatre for three consecutive days [16], where they played pieces like “Song of the Fishermen”, “Hula Dance” and “Dixie”. The newspapers described their performances as “spectacular” and “splendid”, thus showing the public’s appreciation and recognition of the culture of musicals.

Apart from Chinese troupes, foreign troupes had also visited Hong Kong. On 21st June 1933, The Industrial & Commercial Daily Press published the headline “The Hollywood Troupe is Back” [17] and included extensive coverage of the then world-renowned American song-and-dance troupe, which was supposed to pass through Hong Kong, with no intention of staying to perform. However, after repeated requests from the Tai Ping Theatre, the troupe finally agreed to perform in Hong Kong for four days. Moreover, the journalist added, “it is said that the performance would be a sexy, flirtatious one”, “far more exciting and sensual”. Not only did this reflect the characteristics of foreign troupes, but it also demonstrated the locals’ approval of performance with such openness. In 1936, the Central Theatre offered to invite a German art performing troupe to perform in Hong Kong. Press reports described the performance as “an astonishing feat” and “mesmerising”, and even boasted that “no one could refrain from praise after seeing it”, and it is worth noting that the performance was deliberately timed to coincide with the screening of the Hollywood Party (1934). [19]

The presentation of musical films also began to incorporate foreign elements. Released in 1935, Opera Stars and Song Girls (aka Dancing Girl) is a good example. The plot is based on the story of a stage star, played by Tse Sing-nung, who has to resort to shining shoes on the street due to unemployment to make ends meet and care for her sick mother and sister. However, with his beautiful voice, he makes plenty of money and gains recognition from the troupe’s leader, who invites him to perform with the then-famous singer Chan Suet Heung in the musical Wedding. Furthermore, in this “play within a play”, a new American Broadway-style musical is adopted, with dancers from Guangzhou and Hong Kong playing female court attendants dressed in western costumes with Cantonese opera butterfly helmets, while Tse Sing-nung is dressed as a Western Prince Charming. On 4th March 1935, Opera Stars and Song Girls was previewed in King’s Theatre [20]. At the time, the press described it as “a masterfully directed film with more advanced lighting and sound settings than the company’s previous productions” and “an alternative approach to music”, and it was rated as “highly appreciated by the audience”, with a strong message behind, it showed the stars and the girl singers being faithfully committed to fulfilling their theatre mission despite their plight [21]. It is no wonder that a month after its release, it was still “packed with audiences” and “the seats are well-taken”. [22]

The women in the film are dressed in a way that breaks the mould of tradition, getting into the western culture and breaking free. For example, the special issue promoting Stage Romance, described the film: “three-month filming, a budget of $50,000, ten performances and two hundred beautiful women”. As seen from the film stills, the film had a huge cast. Whether it be the dance poses, positions, or costumes, they were all very similar to a Hollywood production. In the film issue, apart from film stills, there are also illustrations, which are able to capture the characters’ very likeness, depicting the three Fo brothers in Indian costume, heads wrapped in white cloth, half-naked, while Lam Oi Ling is depicted as a sexy woman wearing a veil in a graceful pose. (See Figure 4) The music scores of the songs in the film are also shown in the special issue.

Figure 4: The three Fo brothers in the film are depicted in Indian costume, heads wrapped in white cloth, half-naked, while Lam Oi Ling is depicted as a sexy woman wearing a veil in a graceful pose. (Stage Romancespecial issue, 1938)

Eighth Heaven, released in 1939 and starring Tong Suet-hing and Sit Kok-sin, was the highest box office hit of the year in Hong Kong [23]. It describes the anecdotes of the heroine, a Cantonese opera star, about choosing her husband [24]. In the film, songs are arranged to align with the plot. As if by chance, the film was released on Christmas Day, which the newspapers described as “a great silver gift” [25]. In terms of promotion, it is a musical set at one of the most important western festivals—Christmas, thus western elements are incorporated in it. As seen in the film still, the heroine, Tong Suet-hing, is dressed in a western costume, and her attendants are also dressed in similar costumes, with Tong in the centre as if she were in a cluster of flowers (See Figure 5). Their look and stage poses are fairly similar to western musicals; that being said, apart from imitating the west, the film still managed to maintain the oriental style. As seen in the film stills, the male and female characters, Tong Suet-hing and Sit Kok-sin, would wear Cantonese opera costumes and sing Cantonese songs in certain scenes.

Figure 5: Eighth Heaven was described as “a beautiful film with glamorous settings” and “an extraordinary film in southern China”. (Artland, no 44, 15 December 1938)

To conclude, the origins and development of the Hong Kong musicals of the 1930s were closely linked to women’s circumstances, from being oppressed to rising to the stage. Through singing and dancing, they revealed the social and personal conditions they faced and then later were able to break the traditional image of women and gradually become more open and westernised. In terms of the film’s tone, the musicals in the 1930s still retained their Chinese characteristics and did not “go out of tune”. From the 1940s onwards, musical films continued to flourish. The film shot in Hong Kong starring Zhou Xuan was a colour musical film, Rainbow As You Wish (1953, Hsin Hwa), and is said to be the first Chinese musical film in colour. Hsin Hwa Motion Picture Company was also famous for its musical films, such as The Red Lotus (1960), starring Jeanette Lin Cui from MP & GI. The film was shot in Taiwan and Japan, shooting special underwater effects in Japan with the participation of Japanese singers and dancers. Besides, other female stars such as Grace Chang and Jeanette Lin Cui received much attention thanks to their talents, creating a craze for a while. After the birth of the MP & GI and Shaw Bros, the characteristics of musicals were further pushed to the top, allowing the film genre, both exotic and reflective of Chinese culture, to thrive both locally and overseas.

- Lau, L. (劉瀾昌). (2018). Zai heshui jingshui xuanwo zhi zhong: Yiguoliangzhi xia de xinwen shengtai (In the swirl of river and well: The ecology of Hong Kong journalism under the “One country, Two systems”, 在河水井水漩渦之中:一國兩制下的香港新聞生態) (Rev. Ed.). Taiwan: Showwe Information, 165 (in Chinese).

- Zhang, W. (張偉). (2009). Tanying xiaoji – Zhongguo xiandai yingtan de chenfeng yiyu (The dusty corner of contemporary Chinese cinema, 談影小集——中國現代影壇的塵封一隅). Taiwan: Showwe Information, 151 (in Chinese).

- Yeung, K. (楊國雄). (2014). Old publications: Window of the past Hong Kong society (舊書刊中的香港身世). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (Hong Kong) Company Limited, 75 (in Chinese).

- Ibid.

- See note 3.

- Shao, Y. (邵雍). (2006). Zhongguo jindai jinu shi (Contemporary history of Chinese prostitute, 中國近代妓女史). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 313 (in Chinese).

- Wong, S. (黃淑嫻) & Kwok, C. (郭靜寧) (Eds.). (2020). Hong Kong filmography Vol I (1914–1941) (Rev. Ed.). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 295 (in Chinese).

- Shi, D. (史東〉. (1938, December 10). Mantan nanyue gewuban zhong sanchuyan (Something about the three youngsters in Nanyue song-and-dance class, 漫談南粵歌舞班中三雛燕). South China, (南粵) (8) (in Chinese).

- Ibid.

- A Mysterious Night Special Issue, 1937 (in Chinese).

- See note 7, p. 157.

- See note 10.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- (1933, June 20). Lianhua gewutuan shying chunhua (Lotus song-and-dance troupe shooting pornography, 蓮花歌舞團 攝影春畫. The Tien Kwong Morning News (in Chinese).

- (1935, April 5). Gaosheng yan Meihua gewutuan (Plum Flower Dance Troupe in Ko Shing Theatre, 高陞演梅花歌舞團. Chinese Mail (in Chinese).

- (1933, June 21). Haolaiwu gewutuan youlaile (Hollywood song-and-dance troupe coming again, 荷里活歌舞團又來了). The Industrial & Commercial Daily Press (in Chinese).

- Zhongyangyuan xuyan gewutuan (Central Theatre continued to have song-and-dance show, 中央院續演歌舞團), Chinese Mail, 7 April, 1936 (in Chinese).

- Ibid.

- Hongling genu chengji chaojue (Outstanding achievement of Opera Stars and Song Girls, 紅伶歌女成績超絕), The Industrial & Commercial Daily Press, 5 March 1935 (in Chinese).

- Ibid.

- Dongle rengying Hongling genu (Prince’s Theatre still showing Opera Stars and Song Girls, 東樂仍映紅伶歌女), The Industrial & Commercial Daily Press, 2 April 1935 (in Chinese).

- Wei, J. (魏君子). (2019). Guangying le de langhuar: Xianggang dianying mailuo huiyi (Spray in the light and shadow: The retrospective of Hong Kong cinema, 光影裡的浪花:香港電影脈絡回憶). Hong Kong: Chung Hwa Book Company (Hong Kong) Limited, 50 (in Chinese).

- Niyi fengguang de dibatiantang (The beautiful scenery of Eighth Heaven, 旎旖風光的第八天堂), South China (南粵) no 8, 10 December, 1938 (in Chinese).

- Ibid.

1,769 total views